Had the circumstances of our birth been different––born two years later, in South Africa––we would have been a part, the genesis, of the Born Free generation. You know them, those ones that were born after apartheid, into a country governed by Brenda Fassie’s Black President. They were the ones who swam out the womb into a promised freedom––from all oppression and indignity, either by erstwhile white or incumbent Black. The Babies of democracy.

But we were born in West Africa––me in Ghana, her in Nigeria. Still, by virtue of our year of birth, we, too, are, in our own peculiar ways, born free. The year is 1992 and Nigeria holds parliamentary elections for the first time since the 1983 military coup. The year is 1992 and Ghana returns to democracy after a protracted period of rule by a bloodhound. It would take her another seven years, however, to join me in living under a full democracy, so called.

She had just finished serving her country, and was in the capital to see her fiancé. Perhaps they would laugh again over a joke from their introduction ceremony. Maybe she so badly wanted to show him that small thing she’d bought for their wedding which was to follow soon. Or perhaps she’d gone for no reason at all than just to see his face and smell his skin and pinch his flesh.

F-SARS officers barged into the residence looking for Ugwuna, her fiancé. They took her when they did not find him at home. Days later at the station, Ugwuna was informed that she was dead. Her corpse, according to her brother, Alex, showed “signs that she was sexually assaulted.”

Less than a month after, Nigerian people went out onto the streets to seek justice from the state––for her and countless others whose lives have been wasted in similar fashion. They got a massacre instead.

Her name was Ifeoma Abugu. “Ifeoma” means a good, beautiful thing.

––

They mentioned my name among the dead. Moshood. Ademola Moshood. They stood on the podium, before a genuflecting crowd that had raised fists in the air; and in its collective heart, rage and sorrow and hope and love. I was neither on the podium nor in the crowd. I was in Accra, Ghana, on my bed, with my phone. They were at the Lekki-VI toll gate in Lagos, calling out names of youth whose lives had been stolen by armed robbers of F-SARS and the Nigeria Police Force at large.

He, Moshood. Ademola Moshood, was on his way back from work and almost home when he was shot and killed by men of the Nigerian police. March 28, 2019. Surulere, Lagos. After 1 am. A police patrol team had stopped his motorcycle and asked for N200. For refusing to be extorted for no reason, one inspector, a Paul Joseph, cocked his Takorav rifle, and shot him in the head. Ademola Moshood was 34, a member of the Nigerian Legion, he worked with the Ministry of Youth and Sports as a security operative.

––

On October 15, I watched a Punch documentary on the Nigeria Police Force’s murder of 22 year old Jimoh Isiaq. Someone remarked on Twitter that it was these words of Isiaq’s grandfather, Abdulazeez Adeola, said in the documentary, that particularly struck them: “In my own opinion, the government is using thieves to hunt down thieves.”

What struck me were the words of Jimoh Kazeem Jimoh Kazeem, Isiaq’s elder brother. “I plead with Nigerians to get justice for us. This must not be allowed to go unaccounted for. And they should also help us with Jimoh’s wife and child.”

Those aren’t spectacular words. In a country like that, they’re normal, uninteresting. And yet, there is something about the understated nature of the words that arrests me.

March 2019: “We demand that the case should not be swept under the carpet; justice must be served. My brother was married with a kid and his wife is heavily pregnant. We appeal to the state government to come to the aid of his family and ensure that they do not suffer.” ––Hakeem Moshood, elder brother of Ademola Moshood said after the latter’s murder.

I, too, had a Hakeem to my Moshood.

Circa 2004. Hakeem Balogun is on a bus to Lagos. He is traveling back from Eastern Nigeria where he’d gone to complete his last work assignment. In two days, the beginning of a new chapter of his life––in the UK, in pursuit of a PhD. When our father got the call back in Accra, they said it was armed robbers. And that among the travelers that were shot dead was his son, Hakeem. the government is using thieves to hunt down thieves.

Broda Hakeem, Ẹ̀gbọ́n mi, I’m a writer now. Would you, too, think me odd? I think about things like the morphology of words. What does it mean, or is there any meaning at all in the fact that the third syllable of the word for police in Yoruba is the same word for kill?

–

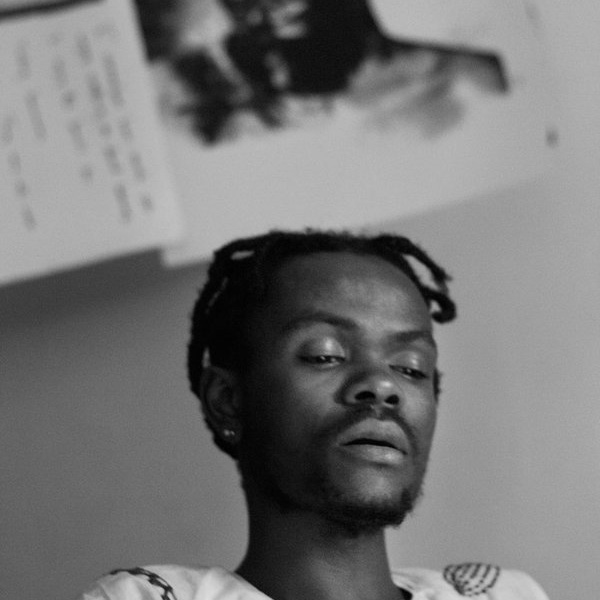

Cover photograph depicts prayers during the ongoing EndSARS protests by the photographer Nyancho NwaNri